When I started working as a developer 25 years ago in Argentina, we were called "Analyst Programmers." We started with problems, not tickets. We sat with clients, figured out what was needed, and delivered a solution. Sometimes that meant building software. The job was solving problems — software was just one way to get there.

Over the years, as organizations grew, we specialized. The stack got complex. Frameworks multiplied. We had backend, frontend, data, infra, etc. Each layer demanded its own tooling, its own patterns, its own mental overhead. So we split ownership. The customer problem got distributed across teams and roles.

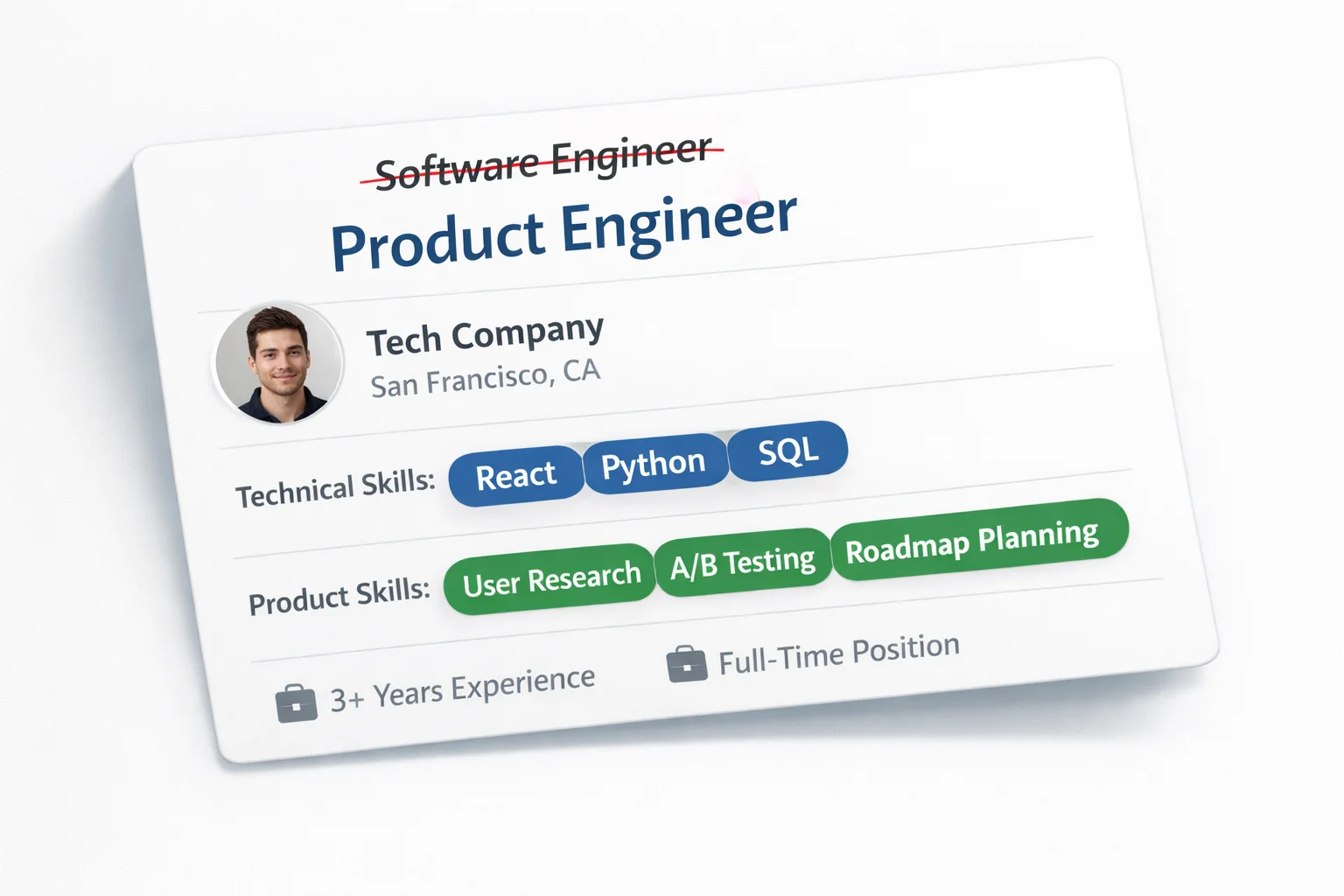

What's a Product Engineer?

Intercom's job description captures it well:

"As a product engineer, you'll be taking ownership of real customer problems by building smart, efficient solutions to both back-end and front-end systems."

The key phrase is ownership of customer problems. Not "implement tickets." Not "build features." Solve problems. Gergely Orosz calls this being "product-minded" — engineers who are curious about the business, not just the code. They ask "why" before "how."

The role emerged from a gap in how product teams work. Luca Rossi describes the shift well: in traditional Scrum, Product Owners handled tactical work — grooming backlogs, writing user stories, managing tickets. Product Managers were supposed to handle strategy: product vision, market positioning, long-term roadmap.

Most teams collapsed these into one PM role. That PM was now responsible for both strategy and writing tickets. Strategy usually suffered.

But in high-performing teams, engineers absorbed the tactical layer. PMs could focus on strategy. Engineers owned execution from design through delivery. The coordination got easier. The feedback loops got shorter.

You can see this in how they work with metrics. PMs focus on lagging indicators — revenue, churn, MAUs. These are outcome metrics. They matter, but they move slowly and respond to many variables at once. Product Engineers focus on leading indicators — feature adoption, activation rates, time-to-value. These predict future outcomes. They're harder to identify but faster to move, which means you can actually iterate on them.

Facebook famously tracked how many users added at least 7 friends, and how fast. That was a leading indicator for long-term engagement. The engineers who owned that metric could run experiments, ship changes, and see results in days — not quarters.

What Product Engineers Actually Do

In practice, owning customer problems means three things:

They run controlled rollouts. Feature flags to release new features to a subset of users. Measure leading indicators before affecting lagging ones. Roll out a new UI to 10% of users, compare engagement, then decide whether to ship to everyone or iterate.

They run experiments. A/B tests when you have volume. Qualitative feedback when you don't. In B2B SaaS with a few customers, statistical significance is a luxury — you measure adoption, watch screen recordings, and talk to users who tried the feature but churned.

They measure outcomes. Post-launch, they track both leading and lagging indicators. Set up dashboards and alerts. Iterate based on real-time data, not quarterly reviews.

The best ones are exposed to customer feedback directly — not through a PM filter. At Clay, engineers spend 20% of their time with customers. When the person who built the feature sees users struggle with it, they fix it differently than when they read about it in a ticket three weeks later.

Back to the Future

Here's the thing: we're not inventing something new. We're rediscovering something we lost.

Those "Analyst Programmers" from 25 years ago? They were product engineers. They just didn't have a fancy title. They sat with customers, understood problems, and built solutions. The code was a means to an end.

Somewhere along the way, we over-specialized. We created handoffs, silos, and endless alignment meetings. We got really good at building things nobody wanted.

Now AI is enabling the comeback of T-shaped/"paint drip" people: deep in one area, competent across many. When tools can scaffold a React component, debug a Terraform config, or explain an unfamiliar codebase, the cognitive load drops. Engineers can work across layers they're not expert in. The T-shape becomes viable again, and with that, owning full customer problems — not just a slice of the stack.

The best teams I work with today are going back to basics — engineers who own outcomes, not just outputs. At the extreme end of this shift are indie hackers — solopreneurs who code, market, sell, and support all on their own. AI is lowering the bar every month. Product Engineers are a step in that direction: engineers who can own problems end-to-end within a team.

We're not inventing a new role. We're remembering an old one.

Looking to Build Product-Driven Teams?

As a fractional CTO, I help companies build and lead remote teams of Product Engineers who drive both technical excellence and business outcomes.

Book a Free Consultation