A startup is growing. The bug count is increasing. Someone, usually a founder or a new VP, looks at what "real companies" do and says: "We need a QA team."

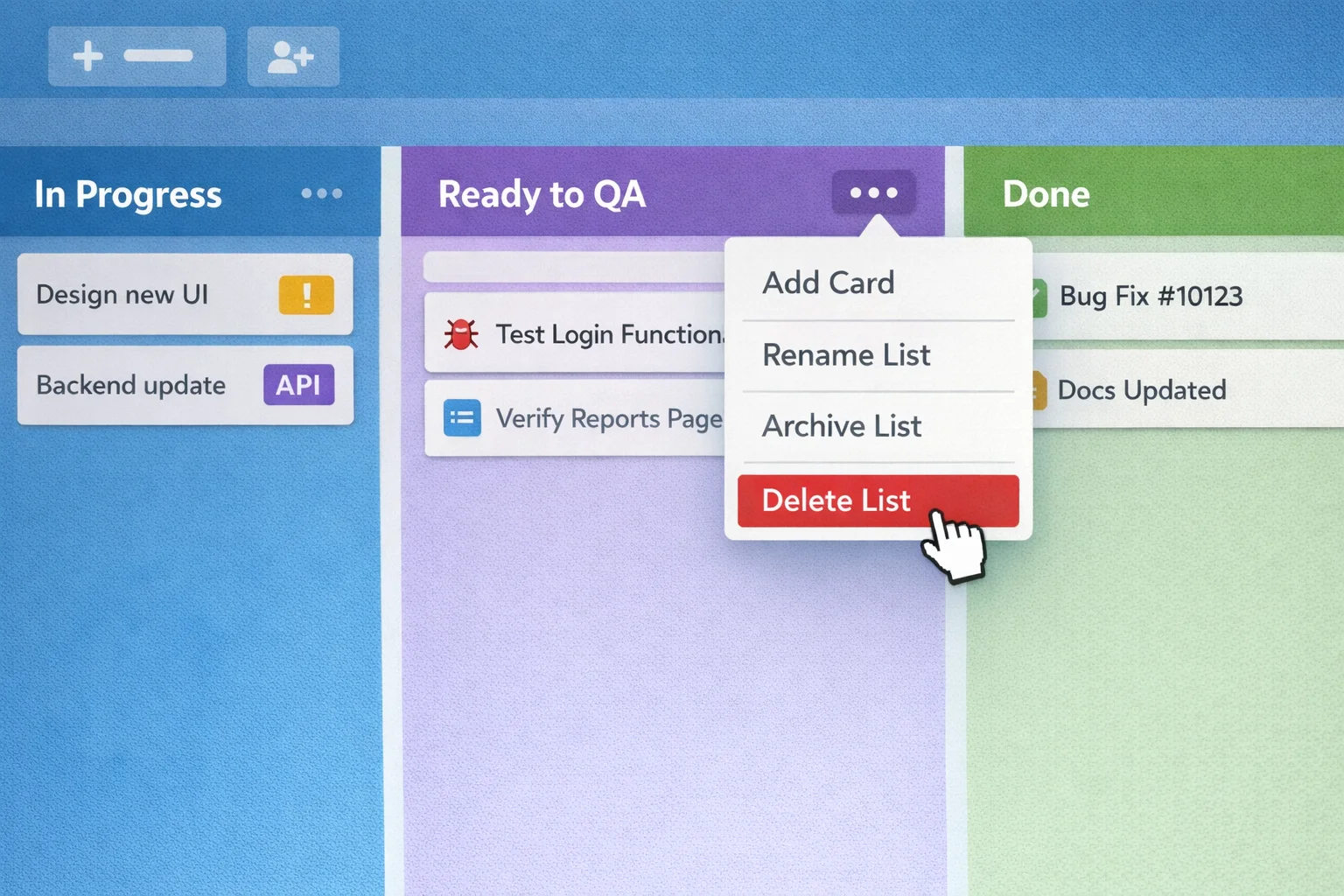

They hire a few testers. Maybe a QA lead. They set up Jira workflows with "Ready for QA" columns. They create test plans.

Three months later, everything is slower. Releases that used to ship in a day now take a week. Developers throw features over the wall and forget about them. Testers find bugs, developers fix them, testers find more bugs. Ticket ping-pong becomes a full-time sport.

And nobody's happier. Not the developers. Not the testers. Not the customers.

The thing is, you probably didn't have a quality problem. You had a process problem. And you just made it worse.

What Big Tech Actually Does

There's this assumption that successful tech companies have armies of testers. That if you want to play in the big leagues, you need dedicated QA.

The data says otherwise.

Microsoft pioneered the SDET role (Software Development Engineer in Test) in the 1990s. They had a 2:1 ratio of developers to SDETs. It was their thing.

In 2014, they killed it.

Why? Because when teams started shipping daily, a separate test role created delays incompatible with continuous delivery. Gergely Orosz described the transition:

"The Skype for Web team became a lot more productive by removing the SDET role."

They threw away tens of thousands of old tests written by the separate test team. Rebuilt their test pyramid. And improved quality, velocity, and engineer satisfaction, all at the same time.

Uber and Netflix? Never had dedicated QA roles for software teams.

Meta? No dedicated QA function for pure software teams.

Google? Engineers own their own quality. They have an EngProd org that builds testing infrastructure, but the testing itself? That's on the people who write the code.

The only Big Tech companies maintaining dedicated QA are Apple and Amazon, primarily for hardware products or slow-release cycles. Not software.

So when your startup hires a QA team because "that's what companies do," you're copying a model that the companies you admire already abandoned.

The Us vs. Them Problem

Separate QA creates a division between the people who build and the people who verify.

Sounds reasonable. Checks and balances. Fresh eyes on the code.

In practice, it creates perverse incentives.

Developers start to think of quality as someone else's job. Why write thorough tests when QA will catch the bugs anyway? Why test edge cases when that's literally what the testers are paid to do? Why care about the user experience when you're measured on tickets closed, not on customer satisfaction?

I've seen developers try to "outsource" even unit tests to the QA team, because in organizations that separate building from testing, testing becomes a lower-status activity.

And I've seen the ticket ping-pong: Dev finishes feature. QA finds bug. Dev fixes it. QA finds another bug. Dev fixes that. QA finds a regression from the first fix. And it repeats until someone decides it's "good enough" and ships it anyway.

That's not a quality process. It's a quality theater.

The Feedback Loop Problem

Will Larson has a framework for thinking about quality where he makes a difference between measuring quality and creating quality.

Errors detected after development handoff are measuring quality. They tell you something went wrong. They don't prevent it from happening again.

Worse: the later you find issues, the more likely you get tactical fixes instead of structural fixes. A bug found in QA gets patched. A bug prevented during design gets designed out of existence.

John Ousterhout defines "errors out of existence" as making illegal states unrepresentable, designing interfaces that can't be misused, catching problems at compile time instead of runtime. This requires design-time thinking. It can't happen after you've already built the thing.

When developers own testing, you get a tight local loop. Write code, write test, see it fail, fix it, see it pass. Immediate feedback. The problem and the solution live in the same brain.

When testers own testing, you get delayed feedback. The problem lives in one brain, the solution in another. By the time the fix comes back, the developer has context-switched to three other features.

The feedback loop isn't just slower. It's ineffective.

QA is a Mindset

Luca Rossi says QA is a mindset, not a role. I love that. It's about knowing what really matters and what doesn't.

And what matters changes based on your product stage.

Pre-product-market-fit, your product changes constantly. Tests easily become a liability rather than an asset. You're not optimizing an existing system — you're discovering what the system should be. Every test you write might need to be rewritten next week when you iterate or pivot.

"Very little QA should be in place at this time. E2E would drag you down because the product changes too fast."

DORA research backs this up. Elite performers do multiple on-demand deployments per day. Lead time for changes? Less than a day. You don't get there with a "Ready for QA" column.

The AI Argument

Now add AI to the mix. It makes having dedicated QA even harder to justify: AI coding tools are making developers increasingly better at testing.

Tools like Cursor and Claude Code don't just write production code. Ask them to add tests to existing code, and they'll identify edge cases you hadn't considered.

This changes the economics. The main argument for dedicated QA was always that developers are too expensive to spend time on testing. But when an AI can scaffold your test suite in minutes, that argument falls apart.

There's a catch, though: AI gets you 80% of the way. The last 20% (edge cases, error handling, production hardening) still requires human judgment. And senior engineers benefit most from AI tools precisely because they know what to look for. They can spot when the AI-generated test is testing the wrong thing, or missing a critical scenario.

AI doesn't replace quality thinking. It amplifies it. And it amplifies it most for the people closest to the code.

What Actually Works

The best teams I know have:

Engineers who own quality. The same person who writes the code writes the tests. Because testing is inseparable from building. You don't throw your code over a wall. You ship it, you monitor it, you fix it when it breaks.

A zero-defect policy. Bugs get fixed fast, even low-priority ones. This is the broken windows theory applied to code: one unfixed bug signals that bugs are acceptable, which invites more bugs. Having few-to-none known defects at any given time makes testing more reliable and morale better. It also makes new bugs easier to spot.

Great integration testing. Integration tests deliver better ROI than end-to-end tests. They're easier to write, easier to maintain, and catch most of the problems that matter. As Guillermo Rauch (fellow Argentine, Vercel founder, and the mind behind Next.js and v0) put it: "Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration."

Good observability + testing in prod. Charity Majors, one of the loudest voices on observability:

"Testing in production is a superpower. It's our inability to acknowledge that we're doing it, and then invest in the tooling and training to do it safely, that's killing us."

Her point: once you deploy, you're not testing code. You're testing systems — users, infrastructure, timing, everything. The only way to know if it works is to watch it work.

This requires a cultural shift. Engineers should be on call for their own code, watching their instrumentation as they deploy. Managers need to speak the language of error budgets and SLOs, to be outcome-oriented rather than zero-tolerance. A system's resilience isn't defined by its lack of errors — it's defined by its ability to survive them.

Distributed ownership. At every company I've worked with, I've promoted dogfooding: PMs and EMs stress-tested early builds. Customer support channeled feedback. Business metrics got monitored in real-time. Everyone cared more about quality when it wasn't "someone else's job."

When Formal QA Makes Sense

Look, don't get me wrong. I'm not saying QA teams are always wrong. They make sense in specific contexts:

- Highly regulated industries. Healthcare, aviation, automotive, where bugs cause compliance violations or physical harm.

- Core banking and payment infrastructure. Systems that directly move money between accounts, not fintech apps that sit on top of Stripe or Mercado Pago. If your payment provider handles the scary parts, your bugs cause bad UX, not financial losses.

- Hardware products. Where you can't push an update after the device ships.

- Slow release cycles. If you ship quarterly or annually, a QA phase is less costly.

- Legacy codebases with little automated testing. If you inherited a mess with no tests, dedicated QA might be necessary while you dig out.

Notice what's not on the list: startups trying to find product-market fit.

If You Already Have QA People

Maybe you're reading this thinking: "Great, but I already hired QA. Now what?"

Redeploy them.

When Microsoft killed the SDET role in 2014, they didn't lay off all their testers. They transitioned them to software engineering roles. And something interesting happened: those former SDETs became unusually effective engineers.

Gergely describes the former SDETs as really good at pointing out edge cases. That's a superpower. People who've spent years breaking software think differently than people who've spent years building it. They see the failure modes. They anticipate the weird user behaviors. They know where bugs hide.

Here's where QA people can add massive value without being a separate function:

- Test infrastructure and platform work. Building CI/CD pipelines, automation tooling, what Google calls EngProd and Meta calls DevInfra.

- Feature development with a quality lens. Embedded in product teams, writing production code and tests.

- Observability and production monitoring. Instrumenting systems and building dashboards.

- Release engineering. Deployment pipelines, feature flags, canary releases.

The goal isn't to eliminate quality-focused people. It's to eliminate the wall between building and verifying. When your best quality thinkers are embedded in the teams that ship code — not gatekeeping after the fact — everyone gets better.

The Question You Should Actually Ask

Instead of "do we need a QA team?", ask: "Why are we shipping bugs?"

Is it because developers don't have time to test? Fix the sprint planning.

Is it because developers don't know how to test? Invest in training and tooling.

Is it because the codebase is so fragile that changes break things unpredictably? Fix the architecture.

Is it because nobody owns quality? Change the culture.

Hiring QA is usually the most expensive solution to these problems — both in direct costs and in the hidden costs of slower feedback loops.

The companies that ship the fastest with the highest quality don't separate building from testing. They integrate them so tightly that you can't tell where one ends and the other begins.

It's not a process. It's a mindset.

There's a famous story from Art & Fear about a ceramics teacher who divided his class in two: one group would be graded on quantity of pots produced, the other on quality. At the end of the semester, guess which group produced the highest quality work? The quantity group. While they were busy churning out pots and learning from mistakes, the quality group sat theorizing about perfection and ended up with little more than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

Software works the same way. Ship more. Learn faster. Quality follows.